To feel better, eat less (yes, even if you’re not overweight)

AFP

For the dwindling few of us who do not actually need to lose weight, the idea of slashing food intake in a bid to extend our healthy lifespan isn’t universally appealing. Hedonists the world over, in fact, have denounced the calorie-restriction-for-life-extension idea as a cruel hoax: the bony, cold and irritable cranks willing to deny themselves the comfort of enough food to maintain their weight probably do not actually live longer, they say: it just feels like their miserable lives go on and on.

Well, here’s a surprise: these people are not miserable. In fact, compared to normal, healthy adults who went about their lives eating what they wanted for two years, normal-weight people who ate 25 per cent less than they wanted for the same stretch of time were happier, less stressed, slept better and had more robust sex drives.

Researchers have long known that when obese people restrict their calories and lose weight, their moods, sleep and sexual function all improve along with many measures of cardiovascular and metabolic health. But the notion that no one with a normal healthy body weight would choose to deliberately forego about 500 calories per day has apparently discouraged anyone from exploring whether calorie restriction would confer the same benefits upon the slim-and-healthy.

But researchers at the Pennington Biomedical Research Centre in Baton Rouge, La., suspected as much. They teamed up with researchers from Duke University, Tufts University and Washington University to conduct a two-year study comparing the effects of calorie restriction on 218 healthy, normal-weight study subjects, almost 70 per cent of them women, ranging between 20 and 57 years old.

The new research was published Monday in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine.

Two-thirds of the participants slashed their normal calorie intake by 25 per cent, while the remaining third went about their lives eating as they always had. In addition to checking their weight and, in men, reproductive hormones, the researchers took detailed measurements of each subject’s mood, sleep quality and sexual function.

By the end of year one, the subjects in the calorie-restriction group had lost, on average, 15.2 per cent of their body weight, and 11.5 per cent of body weight by the end of year two. By the end of the study, the calorie-restriction group’s average BMI was 22.6 — right in the middle of the healthy, normal weight category. Those who continued to eat normally had no change in their weight on average.

Over time, the calorie-restricted subjects reported improving mood compared to their baseline measures, and falling tension levels. Those who had continued to eat normally had poorer moods than the calorie-restricted subjects, and among the few who fell just inside the overweight category (BMI above 25), had worsening depression scores by the end of year two.

On five measures, the calorie-restricted subjects’ perceived sleep quality levels remained the same, while those of subjects who continued to eat as they wished worsened at the end of year one.

By the end of the two-year study, those who had pared their intake reported improvements in their sexual drive and relationships, although men who fed themselves to satiation reported higher arousal scores. At the end of one year, free testosterone levels declined in the men who ate what they wanted, but not in the men whose calories had been pared.

In none of these cases was the average difference between the satiated and the lean-and-hungry large. But they were clear, and judged not to have been statistical flukes. The researchers suggested that physicians could use the findings to reassure their healthy, normal-weight patients that calorie restriction may have some benefits and does not lead to misery.

In a commentary published alongside the new research, Dr Tannaz Moin of the University of California, Los Angeles wrote that the new research underscores the potential importance of measures that head off weight gain and obesity before they happen. Currently, insurers are required to reimburse physicians for screening and counselling their patients for obesity, but the focus has been on patients who already have become obese.

Since it is clear from the new research that normal-weight people can be induced to cut their calories over a long period, maybe, wrote Moin, physicians and insurers should be focusing on prevention in younger adults who are still trim and healthy.

Latest News

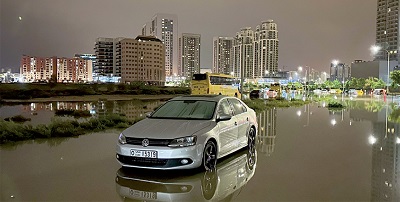

Dubai reels from floods chaos after record rains

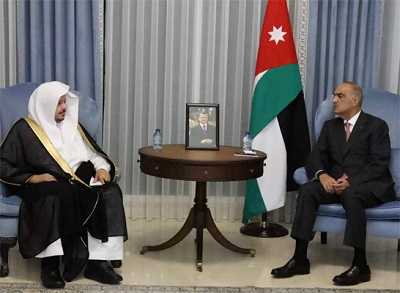

Dubai reels from floods chaos after record rains Khasawneh, Saudi Shura Council speaker discuss bilateral ties, regional developments

Khasawneh, Saudi Shura Council speaker discuss bilateral ties, regional developments Egyptian Foreign Minister condemns potential Palestinian displacement as 'war crime'

Egyptian Foreign Minister condemns potential Palestinian displacement as 'war crime' Travelers from Jordan advised to confirm flights amid Gulf weather turmoil

Travelers from Jordan advised to confirm flights amid Gulf weather turmoil France summons Iranian ambassador over strikes against “Israel”

France summons Iranian ambassador over strikes against “Israel”

Most Read Articles

- Dubai reels from floods chaos after record rains

- Security Council to vote Thursday on Palestinian state UN membership

- King, Bahrain monarch stress need to maintain Arab coordination

- Khasawneh, Saudi Shura Council speaker discuss bilateral ties, regional developments

- Hizbollah says struck Israel base in retaliation for fighters' killing

- Tesla asks shareholders to reapprove huge Musk pay deal

- Jordan will take down any projectiles threatening its people, sovereignty — Safadi

- The mystery of US interest rates - By The mystery of US interest rates, The Jordan Times

- Princess Basma checks on patients receiving treatments

- Knights of Change launches nationwide blood donation campaign for Gaza