Blending fantasy with harsh reality

The Jordan Times

My End Is My Beginning

Moris Farhi

London: Saqi Books, 2020

Pp. 256

Turkish-born Moris Farhi, who died last year, spent most of his life in the UK campaigning for human rights via Amnesty International and PEN international, where he was Vice President and Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee. He was also a prolific writer, penning a number of novels and a poetry collection, as well as writing for the theatre and screen. His creative talents and broad cultural background shine brightly in this, his last novel, “My End Is My Beginning”.

Written in prose that often approaches poetry, the novel is a love story between the two central characters, Belkis and Oric. It is also the story of an all-encompassing love for humanity that drives them, along with a small group of rebels, to travel around the world confronting injustice and cruelty and saving the victims. This is the age of dictators and the abuses they unleash are easily recognisable as the political, social, environmental and human catastrophes that plague the world today, from genocidal wars to drug addiction. While Farhi has employed fantasy to write the story in the style of a myth, its essence is hard-core reality. More than one dictator is easily recognisable, as are cultural figures and known advocates of human rights, such as Hrant, Belkis’s and Oric’s mentor. He is obviously Hrant Dink, the prominent Armenian-Turkish intellectual and newspaper editor who advocated Turkish-Armenian reconciliation and human rights overall, and who was assassinated in Istanbul in 2007.

The dictators in the story are dubbed “the Saviours” who are trying to impose their “Big Lies” on the population at large, using race, religion, ethnicity and gender differences to divide and rule. Their attempt comes to a head as the tyrant Numen, who supposedly advocates progressive Western policies, seals an alliance with the leader of an oil-rich “Islamic republic” who is peddling a distorted version of religion. In a protest against this unholy federation, Balkis is killed by the dictator’s guards, while Oric is overwhelmed by guilt at having become paralysed by fear and not done enough to save her.

Echoing the novel’s title, this is not the end of the story but only the beginning. Belkis and Oric are Dolphineros who live by the mantra, “Death is a lie”. When they are killed, they become Leviathans, wise leaders who enjoy eternal life and can be repeatedly reincarnated; according to Belkis, “the men and women who envisioned a better world and are now guiding us”. (p. 158)

In Hrant’s words, “Our mission is to hold Life sacred… We toil for a future where killing will be a bygone pandemic”. (p. 37)

Belkis continues to reappear as Oric struggles with his guilt and tries to overcome the fear that caused it. Cloaked in various disguises, they join other non-violent fighters for freedom on missions to many distant lands, aiming to repair the world. Oric begins to keep a journal chronicling their journeys, perhaps the author’s way of pointing to the significance of the written word in recording real history and guiding people towards change.

Combatting modern slavery, they travel to Africa to free boys for sale as child soldiers, youth trafficked for the sex trade, imprisoned journalists and activists, adults sold for organ transplants and girls who had been abducted. In Asia, they rescue women ensnared for the European sex trade, men in debt bondage and imprisoned dissenters, journalists, writers and bloggers, Rohingyas facing ethnic cleansing, Afghani youth recruited by the Taliban, Indian children slaving in cottage industries, and many more. In Central America they save those targeted for assassination by the drug cartels. In Yemen they rescue orphans in war-torn Yemen. They also liberate Filipino, Bangladeshi and Indonesian domestics, and aid refugees on the Greek island of Lesbos. The list goes on and on, and each mission is an adventure and a lesson in itself. There is also time for friendship and beauty as they join Roma friends for evenings of feasts, song and dance, and stage cultural festivals for marginalised social groups, which proved that “art did melt away animosities, that whatever the differences between peoples and cultures, the joy of humanness overpowered the hatreds concocted by deranged power-merchants”. (p. 213)

As one reads along to find out if Oric will overcome his fear and guilt, Farhi mesmerises with his multiple references to ancient and medieval mythology; he delights with his satirising of fundamentalisms of all shades; and impresses by paying homage to artists, writers, philosophers, humanists, doctors, scientists, explorers and philanthropists who have paved the way to a better future. While portraying a dystopia in all its gruesome features, Farhi also shows the way to freedom and equality via love, compassion and reason.

Latest News

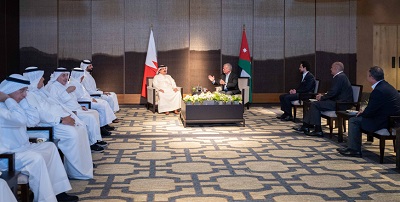

King, Bahrain monarch stress need to maintain Arab coordination

King, Bahrain monarch stress need to maintain Arab coordination Security Council to vote Thursday on Palestinian state UN membership

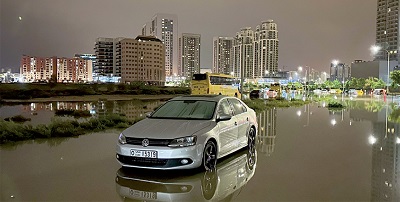

Security Council to vote Thursday on Palestinian state UN membership Dubai reels from floods chaos after record rains

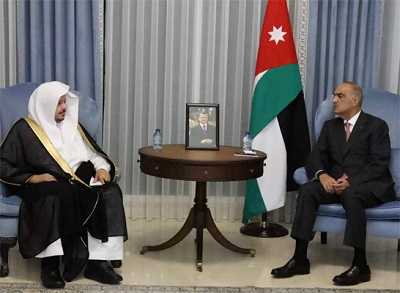

Dubai reels from floods chaos after record rains Khasawneh, Saudi Shura Council speaker discuss bilateral ties, regional developments

Khasawneh, Saudi Shura Council speaker discuss bilateral ties, regional developments Egyptian Foreign Minister condemns potential Palestinian displacement as 'war crime'

Egyptian Foreign Minister condemns potential Palestinian displacement as 'war crime'

Most Read Articles

- King, Bahrain monarch stress need to maintain Arab coordination

- Dubai reels from floods chaos after record rains

- Security Council to vote Thursday on Palestinian state UN membership

- Khasawneh, Saudi Shura Council speaker discuss bilateral ties, regional developments

- Tesla asks shareholders to reapprove huge Musk pay deal

- Jordan will take down any projectiles threatening its people, sovereignty — Safadi

- Hizbollah says struck Israel base in retaliation for fighters' killing

- Princess Basma checks on patients receiving treatments

- Knights of Change launches nationwide blood donation campaign for Gaza

- The mystery of US interest rates - By The mystery of US interest rates, The Jordan Times