Israel’s relations with Jordan are at a low point yet again. Crown Prince Hussein bin Abdallah’s visit to Jerusalem’s al-Aqsa Mosque was cancelled in early March because of a disagreement with the Israeli authorities on the size and composition of the accompanying Jordanian security detail. The Jordanians were offended and retaliated by refusing permission for Netanyahu’s use of Jordanian airspace for his flight to the UAE, at the height of his most recent election campaign. Netanyahu replied with a decision to punish the Jordanians by refusing to answer their request for an additional share of Israeli water to help address Jordan’s chronic water shortage. Though the Jordanians are presently struggling with a most severe outbreak of COVID-19, their worst since the beginning of the epidemic, after having been fairly successful in containing the virus, Israel has not come forth with any offers of assistance. A generous supply of vaccines, for example, would have been the obvious thing to do if relations were as they ought to have been between two neighbors at peace with each other for a quarter of a century.

Netanyahu’s poor relationship with the Jordanians has a long history. It started on a sour note, when Jordan’s first Ambassador to Israel, Marwan Muasher, met with Netanyahu, shortly after Israel’s 1994 peace treaty with the Hashemite Kingdom. Netanyahu explained to Muasher that Israel and Jordan had a common cause to prevent the establishment of a Palestinian state. Muasher hastened to correct Netanyahu and to argue that actually Jordan had a supreme interest in such a Palestinian state so as to ensure that the Palestinian problem would be resolved in the West Bank and Gaza, and not at Jordan’s expense. Netanyahu responded by telling Muasher that it was he, Netanyahu, who understood Jordan’s position better than the Ambassador, a display of conceit and arrogance that Muasher never forgot.

King Hussein, nevertheless, was not negatively predisposed towards Netanyahu. On the contrary. Hussein did not trust Shimon Peres, whom he suspected of pro-Palestinian tendencies. After Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination, in the run-up to the May 1996 elections, Hussein actually wanted Netanyahu to win. When Netanyahu defeated Peres many in the Arab world were most disenchanted. But not Hussein. He urged his fellow Arab leaders to give Netanyahu a chance.

Hussein’s disappointment with Netanyahu was rapid and complete, and within a few months he had lost faith in the new Israeli Premier. At the end of September 1996, asserting Israeli control of the old city, Netanyahu decided to open the Hasmonean tunnel in East Jerusalem, resulting in bloody clashes between Israeli forces and Palestinians in which 15 Israeli soldiers and 60 Palestinians lost their lives. The Jordanians, needless to say, were fervently opposed to the Israeli decision and they condemned it virulently, especially due to the fact, that just the day before, Netanyahu’s policy advisor, Dore Gold, had visited Amman. Gold did not apprise the Jordanians on what was about to happen in Jerusalem, but just the meeting in itself could have created the impression that the Jordanians had given the go-ahead for the Israeli move, causing them unnecessary embarrassment.

Shortly thereafter, in early October1996, President Clinton invited Hussein, Arafat and Netanyahu to a summit in the White House in an effort to jumpstart the peace process which was going nowhere. Hussein was devastating in his criticism of Netanyahu. In the presence of the other guests the king expressed his profound disappointment with Netanyahu, accusing him of being unable to rise to the historical occasion, lacking the vision that had guided Rabin. Hussein was relentless. In February and March 1997 he sent two letters to Netanyahu after the king had failed to persuade the prime minister to refrain from new building projects in East Jerusalem. Hussein explained that he had lost all confidence in Netanyahu, who did not keep his word, was not a partner nor a true friend.

In September 1997 Israeli Mossad agents botched an assassination attempt on Hamas leader Khalid Mash’al in Amman. Hussein was livid with rage. He was convinced that the Israeli action was deliberately designed by Netanyahu to derail Hussein’s attempts to further the peace process with the Palestinians, which was so critical for Jordan’s national security. Whatever grain of trust that might have remained between the two leaders finally disappeared.

In April 1998 Hussein wrote to Netanyahu yet again. He warned against the continued stalemate that could endanger the entire region which might be engulfed by “an era of darkness.” Rabin’s departure, the king continued had altered the equation. Arabs and Israelis had changed places. Once it was the Arabs who engaged in empty talk and “provoked the entire world” against them. But now the Israelis had taken their place.

King Abdallah inherited his father’s negative attitude towards Netanyahu. When Netanyahu returned to the premiership in March 2009 Abdallah became especially pessimistic. In an interview a year later he described relations with Israel as their worst ever since the signing of the peace treaty. The continuation of settlement activity in the West Bank and projects that were changing realities on the ground in Jerusalem worsened relations with Jordan and were at the root of constant Jordanian complaints against Israel. President Trump’s “Deal of the Century” only added fuel to the fire.

Jordan was kept in the dark during the preparation of the US initiative. When in December 2017 Trump announced his intention to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and to transfer the US embassy from Tel Aviv, the Jordanians became increasingly apprehensive about the US plan. In October 2018, in a move calculated to register their displeasure with the unfolding developments, the Jordanians announced their refusal to renew the special land usage arrangements, a gesture of goodwill that had been included in the peace treaty, for Naharayim and Zofar, that allowed Israelis to work on land under Jordanian sovereignty.

The Jordanians had no expectations from the “Deal of the Century.” Netanyahu’s talk on annexation of the Jordan Valley and other parts of the West Bank, in conjunction with the US plan, and during the recent election campaigns in Israel, were understood in Jordan as a design to preclude all and every possibility for the creation of a viable Palestinian state and as an unstoppable shift towards a one-state reality. In the Jordanian analysis one state was not a solution but a recipe for endless Israeli-Palestinian friction and conflict that could eventually spill over across the river and endanger the stability and security of the kingdom.

The Abraham Accords with the UAE and Bahrein have removed the threat of annexation from the agenda for the meantime, much to the relief of the Jordanians. Feelers were recently put out by both sides to improve relations and the foreign ministers of the two countries met a few times. But these small steps of progress were set back by the cancellation of Crown Prince Hussein’s visit and the ensuing tit-for-tat of reprisals and counter-reprisals between the two countries. The cancellation of the visit for rather marginal technical reasons is indicative of the poor state of the relationship, if the leaderships are incapable of mending hitches of this nature as a simple matter of course.

On Netanyahu’s watch, over a long period of time spanning three decades, Israel’s relationship with Jordan, so critical for Israel’s long-term security in facing challenges from the east, has been allowed to flounder. Since Rabin’s assassination three generations of the Hashemite royal family, Hussein, Abdallah and now Hussein bin Abdallah, have been exposed unnecessarily to Israeli policy mismanagement, disappointment, surprises and insults, to the extent that in Jordan of today Israel is seen less as a reliable strategic partner and more as a potential threat. That does not bode well for either side, certainly not for Israel. Whatever Israel’s new government may be, it must have the improvement of ties with Jordan as a top priority, first and foremost for Israel’s own sake.

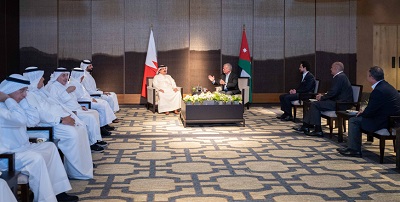

King, Bahrain monarch stress need to maintain Arab coordination

King, Bahrain monarch stress need to maintain Arab coordination Security Council to vote Thursday on Palestinian state UN membership

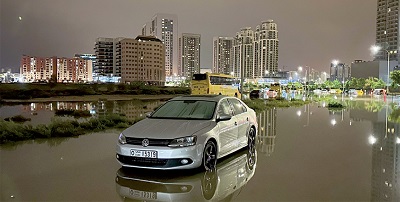

Security Council to vote Thursday on Palestinian state UN membership Dubai reels from floods chaos after record rains

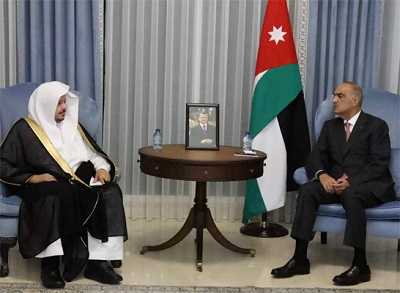

Dubai reels from floods chaos after record rains Khasawneh, Saudi Shura Council speaker discuss bilateral ties, regional developments

Khasawneh, Saudi Shura Council speaker discuss bilateral ties, regional developments Egyptian Foreign Minister condemns potential Palestinian displacement as 'war crime'

Egyptian Foreign Minister condemns potential Palestinian displacement as 'war crime'