From 1917 until the late 1980s, Moscow’s interventions in conflicts around the world were driven by a desire to promote communist ideology. Since the fall of Soviet Union, the Kremlin has failed to make clear what added value, if any, Russian intervention could bring to the international scene. To better establish itself as a world leader today, Russia knows it needs to rebrand itself.

Whereas the West tends to justify its interest-based intervention in the Middle East by explaining its efforts as democracy promotion, Russia has pursued its interests in the region by trying to present itself as a problem solver. While it has been successful in reducing tensions in Syria, Russia’s conflict-mediation approach tends to be effective in freezing conflicts rather than resolving them.

Russia’s involvement in Syria provides the best example of its efforts to emerge as a Middle East problem solver. Since the beginning of Russia’s Syrian military operation in 2015, Moscow has noticeably stepped up its participation in the negotiation process. Moscow’s efforts led to the creation of a powerful triple alliance of Russia, Iran, and Turkey, which formed the basis of the Astana negotiation process, as well as the Syrian people’s congress in Sochi. In 2017, Moscow began to look for alternative venues to launch a specific dialogue with Syrian opposition groups in Cairo (with Jaysh al-Islam and Jaysh al-Tawhid) and Geneva (with Faylaq al-Rahman), as well as to negotiate with the United States and Jordan in Amman.

Russia has also tried its hand at mediating the impasse between the two main rival governments in Libya. While receiving eastern strongman Khalifa Haftar on three occasions and printing money for his parallel central bank in Bayda, Russia likewise received his Tripoli-based rival, hoping to play an intermediary role and bridge the divide between the Haftar and Fayez al-Serraj, who leads Libya’s internationally recognized Government of National Accord. Furthermore, Russia presented itself as a mediator in other intra-Libyan conflicts including launching a dialogue between the GNA and the tribes that control the southwestern city of Ubari.

As a diplomatic crisis and blockade has divided the Gulf countries, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has visited both Saudi Arabia and Qatar several times, announcing Moscow’s full support for Kuwait’s mediation and a negotiated resolution to the crisis. This soft intervention led to the first-ever visit to Russia by a Saudi king, an important signal that the two countries are finally overcoming a long-troubled relationship dating back to their confrontation in Afghanistan in 1979.

Moscow is even wading into Israeli-Palestinian diplomacy. Immediately after U.S. President Donald Trump’s decision to move the U.S. Embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas cut relations with the White House and paid a state visit to Moscow. While receiving Abbas in Moscow, Putin called Trump to encourage Washington to pursue peace efforts while also offering Moscow’s help. Furthermore, during the Arab League summit — also dubbed the Al-Quds summit to emphasize the rejection of the U.S. Embassy move — Putin sent a letter to the Arab leaders stating that “Russia is ready to develop cooperation with the League of Arab States by all possible means to ensure regional safety.”

In theory, Russia’s mediation should help resolve the Middle East’s conflicts. Russia’s involvement could potentially end the monopoly of unilateral American mediation that has traditionally failed to resolve regional disputes — such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict — and instead exacerbated them. However, Russia’s approach to conflict resolution is better at freezing conflicts than ending them. This dynamic is evident in several conflicts that Russia has attempted to tackle, namely in Crimea, Ukraine, Georgia, and Chechnya. By using force, Moscow was able to impose unilateral solutions to these conflicts but failed to address their underlying causes. Unless the root causes of these conflicts are addressed, the most this approach will ever achieve is a fragile peace, or what Johan Galtung calls a “negative peace.” In fact, what Russian military intervention achieved in these conflicts was to structurally transform them by creating a severe imbalance of power between the parties which, in turn, left no room for resolution.

Russia has done the same in Syria, where it enabled the Assad regime to achieve a decisive victory in the Battle of Aleppo, thereby leaving no incentives for the government to engage in talks and no hope for the opposition to achieve some of their demands through negotiated solutions. It’s no wonder that most of the Syrian opposition refused to participate in the Russian-brokered Sochi peace talks. Solutions achieved under a severe power imbalance, especially those achieved through massive military might, are difficult to sustain.

Conflicts can be suppressed for a while but will likely erupt again once those power relations change.

Since the beginning of Russia’s military presence in Syria, Moscow has managed to reduce the scope of the conflict. Nonetheless, the Russian presence in Syria has failed to improve the lives of Syrians so that they can be partners in achieving a lasting resolution to their civil war. Rather, it has prevented them from holding a national dialogue and seeking some form of reconciliation.

By helping Bashar al-Assad eliminate nearly all opposition to the Syrian regime, Russia has not allowed any opportunities for transitional justice in Syria, which is a key factor for the durable resolution of any conflict. To date, Assad seems like an absolute winner in the war, and he is not constrained by any obligations, either domestic or international, to the militarily defeated opposition.

Russia’s solutions are also imposed from the top down in partnership with entrenched regimes and brutal dictatorships rather than with bottom-up forces that aim to change the status quo. Moscow has prevented the ruthless Assad regime from collapsing, supported Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s regime in Egypt, and Haftar’s in Libya. Russia’s military and diplomatic involvement generally rewards dictators who are seen to serve Russia’s interests rather than supporting citizens’ calls for freedom and justice, thereby exacerbating the tensions that led to these revolutions in the first place.

Since the mass protests at Moscow’s Bolotnaya Square in 2011 and 2012, the Russian political establishment has actively promoted the idea that stability should serve as the key measure of the effectiveness of any political regime. The events of the Arab Spring seemed to confirm this thesis: Assad’s dictatorship fended off the Islamic State; Sisi’s military regime prevented rule by the Muslim Brotherhood; and post-Arab Spring realities in Libya and Yemen are similarly bleak. Vladimir Putin has used this as evidence that stability matters more than justice.

Resolving conflicts in a lasting manner generally requires a serious financial commitment, something that Russia’s interventions lack.

Russia cannot finance a reconstruction process or offer a Marshall Plan for Syria. Silencing conflicts, however, has allowed Russia to hedge its bets, maintaining its own interests (such as the military bases in Tartus) while engaging with the various warring parties. Russia does not have any clear long-term strategy in the Middle East. It has situational interests, and the desire to take advantage of the current political moment, but it lacks a coherent, long-term vision of what a new regional order should look like.

Unlike in the heyday of communism, Russian foreign policy today suffers from an ideological vacuum. This lack of any guiding principles has led to an extremely reactionary approach. Russia is not yet able to formulate a clear agenda of its own, so its actions are primarily a reaction to the West. The most important message that Russian foreign policy sends to the Middle East and the world is that Moscow will fill a vacuum wherever the West has failed, even if this means producing situations where conflicts are suppressed rather than resolved.

Latest News

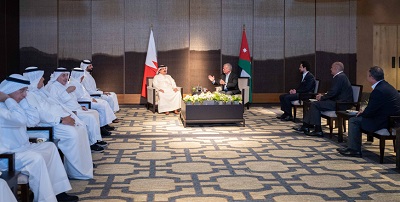

King, Bahrain monarch stress need to maintain Arab coordination

King, Bahrain monarch stress need to maintain Arab coordination Security Council to vote Thursday on Palestinian state UN membership

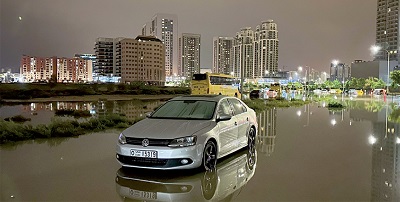

Security Council to vote Thursday on Palestinian state UN membership Dubai reels from floods chaos after record rains

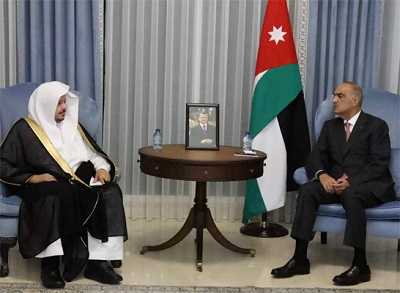

Dubai reels from floods chaos after record rains Khasawneh, Saudi Shura Council speaker discuss bilateral ties, regional developments

Khasawneh, Saudi Shura Council speaker discuss bilateral ties, regional developments Egyptian Foreign Minister condemns potential Palestinian displacement as 'war crime'

Egyptian Foreign Minister condemns potential Palestinian displacement as 'war crime'

Most Read Articles

- Senate president, British ambassador discuss strategic partnership, regional stability

- Jordan urges UN to recognise Palestine as state

- JAF carries out seven more airdrops of aid into Gaza

- Temperatures to near 40 degree mark next week in Jordan

- Safadi, Iranian counterpart discuss war on Gaza, regional escalation

- UN chief warns Mideast on brink of ‘full-scale regional conflict’

- US vetoes Security Council resolution on full Palestinian UN membership

- Google fires 28 employees for protesting $1.2 billion cloud deal with “Israeli” army

- Biden urges Congress to pass 'pivotal' Ukraine, Israel war aid

- Israeli Occupation strike inside Iran responds to Tehran's provocation, reports say