Jordan in race against time to re-penetrate Iraqi market as regional competitors scramble for footholds

Abdul Rahman Bazian , The Jordan Times

AMMAN/BAGHDAD — The governments of Jordan and Iraq, two weeks ago, concluded talks to facilitate economic, trade and power cooperation and development, including three major trade agreements, aside from the memorandum of understanding on power linkage.

According to Prime Minister Omar Razzaz, two of those trade accords will reflect positively on Jordanian exports to Iraq within the upcoming months, mainly the restoration of custom exemptions for Jordanian goods that do not compete with Iraqi products and the door-to-door freight transport agreement.

It will “substitute the back-to-back freight shipping mechanism, which is inefficient, both in terms of cost and time wasted”, the premier explained to the reporters he met on the sidelines of his visit to Iraq.

Entailed in these new trade measures are new allowances to ease visa protocols for freight transport through the Karameh-Turaibil Border Crossing, he added.

Iraqi Minister of Industry and Minerals Saleh Jubouri also sounded hopeful when he told The Jordan Times that he expected Jordanian exports to Iraq to double in 2019.

Notably, exports to Iraq dropped from nearly JD883.1 million in 2013 to around JD367.7 million in 2017, followed by a 36 per cent increase in July 2018, compared with the same month in 2017.

Nonetheless, “the Iraqi market is overrun by Turkish products, as well as Iranian exports, though to a lesser extent”, Jubouri warned.

Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries are now exporting to Iraq, a source with the direct foreign investments office at the Jordanian Embassy in Baghdad told The Jordan Times. Jordan is not going to be without competition in its pursuit of a slice in the Iraq reconstruction project, Razzaz acknowledged.

However, head of the Direct Investment Department at the Jordanian Embassy in Baghdad Riyad Ababneh argued that “Iraqi consumers have confidence in Jordanian products, which is an advantage for [our] exports over competitors’”.

Against reassurances by Iraqi Ambassador to Jordan Safia Al Suhail on the outstanding trade relationship between Iraq and Jordan and the promises of exempting Jordanian exports, Jubouri subtly reaffirmed that the issue of costs may very well prove to be a challenge for Jordanian exporters to secure a significant share of the Iraq market.

To that, Razzaz promised that the industrial estate agreed to be built on the border during the talks, over an area of 24 square kilometres, would drastically cut costs for exports and boost bilateral trade ties between the two countries.

Additionally, Razzaz and his Iraqi counterpart, Adel Abdul Mahdi, announced work was underway to settle Iraqi debts to Jordanian enterprises and claims dating back to the era of the trade protocol before the occupation of Iraq in 2003.

Still, some industrialists and exporters, as well as economists, remain sceptical of the practical outcomes of all these pledges, despite the fixed timeline set by both governments for the implementation of these agreements, to launch on February 2, according to the joint statement issued at the conclusion of December 29-30 visit, last year.

High expectations

Most of the deals signed are old agreements, merely renewed, economist Mazin Marji highlighted.

“None of it is bad for business. Some will help, yes, but in reality I think restoring the scale of Jordanian exports to 2013 levels, before the border closure, is not doable within a year, or two for that matter. In three years, maybe,” he argued, “provided that the current political, security and other variables do not change, let alone restoring the volume of exports to pre-occupation levels”.

Economist Mufleh Akel agreed.

“The [Iraqi] minister’s expectations are a little too optimistic,” he said.

Talking about restoring the glorious days of exportation to Iraq, however, is an entirely different story, according to the economist.

“The truth is that the pre-occupation Iraqi authorities imposed Jordanian products on the [Iraqi] market, granting [our] exporters an absolute advantage, especially under the oil-for-food programme, which was an internationally endorsed agenda. We need not forget that the Iraqi leadership was willing to overlook the shortcoming quality of our exported goods in favour of supporting Jordan,” Marji said.

“This is no longer the case.”

Jordan does not any more have an absolute advantage over other competitors in the Iraqi market. “We need to look to our comparative, relative advantage and capitalise on it, that is if indeed we wish to restore our share of the Iraqi market,” he added.

One of the issues facing the Jordanian exports economy, Marji explained, is that the private sector wants the government to secure the market share for their exports, instead of competing for it.

“This is not going to happen. Competition over Iraq is intense,” he added.

“Exemptions for Jordanian goods will help boost exports, but the whole door-to-door, instead of back-to-back freight shipping arrangement, is merely a technicality. Combined, they probably will make a difference, but ever so slightly. For one, Jordanian commodities are not competitive in terms of quality or price. Two: We do not produce enough of the products that actually do have a market in Iraq.”

Noteworthy is the fact that the exemptions decision is not a new one, said financial economist, head of Al Ghad's business department and columnist, Yousef Damra.

“Jordan used to export more than 500 products exempt of custom duties and fees to Iraq. This agreement cuts the list of exempt Jordanian exports to a little over 360 products,” he noted.

Vice Chairman of Petra Engineering Industries Company and Jordanian Exports Association President Omar Abu Wishah believes otherwise, namely, that the door-to-door arrangement will increase the operational capacity of the land shipping sector.

In regards to boosting exportation to Iraq, he also believes it can be done in a year’s time.

“In fact, with the exemptions, and if we really play fair-game with our competitors, it is possible that Jordan doubles it exports to Iraq within 2019,” he said.

His position is that there are a number of quality Jordanian products that the Iraqi market can absorb, provided that costs are cut to boost competitiveness, and that Jordanian exports can be set to rival even Turkish producers.

It is not that the Jordanian private sector is relying on the government to secure a share in the Iraqi market for them, he said, but rather “that much of the costs of producing and exporting to Iraq are controlled by government regulation and policy. The government has a part to do in this”.

“Authorities need to facilitate exportation to Iraq and cut costs, which include power and transportation costs,” he said.

If the costs of manufacturing, production and transport are not optimised to boost exporter profitability, the quality of the products in export will be questionable and the overall operation may not be feasible for exporters to engage, he argued.

“This is aside to the issue of taxation under the new Income Tax Law. The government has to compensate for these increased costs, all of them, for businesses to retain a level of profitability that would allow them to export with ease,” Abu Wishah underlined.

Without such exemptions, facilities and privileges, he insisted, Jordan will never be able to compete with Turkey, Iran, the US or the Saudis and Emiratis in Iraq.

Akel agrees that the door-to-door mechanism will help boost the profitability of exportation for Jordanian producers, but argues that exports lack competitiveness as well.

“Aside from the absolute economic overlord in Iraq, [the] US, Jordan is up against the Iranians and the Turks, in a race for the Iraqi market. We are on relatively good terms with the Iranians, who have political leverage in Iraq to funnel their products, and the price offering to back its competitive advantage. The Turks, on the other hand, have the combined advantage of quality and pricing,” he said.

To that, Media Minister and Government Spokesperson Jumana Ghunaimat confirmed during the closed press meeting with Razzaz in Baghdad that work was under way to construct renewable energy facilities for industrial use, to lower the costs of energy for Jordanian manufacturers and exporters.

She also added that the exemptions on the Iraqi side will add to the comparative cost advantage of Jordanian exports.

Doubling down on the reassurances, Razzaz followed up with promises to see the imminent implementation of the oil pipeline, which will allow Jordan to procure 10,000 barrels of oil on a daily basis.

“But is that enough?” Akel asked.

Short on competitiveness

Much of the cost structure is energy, not only in terms of powering structures and industrial facilities, but also in terms of transportation costs, as well as in terms of input costs for manufacturing, he said.

“The oil pipeline will take years to construct, and it will meet Israel’s resistance, for geopolitical reasons that have to do with the Iranian influence and the unsavoury relations between Iraq and Israel. I mean, we have seen this before. The pipeline is an old project that has never come through and is unlikely to see the light of day. And without the low-cost oil, regardless of the pipeline, much of the competitiveness of Jordanian exports will be lost, regardless of the exemptions,” Akel underlined.

As for the industrial estate, “I doubt the Iraqis have much interest in it,” he said.

“The Iraqis want to build their domestic economic and industrial capabilities, and to be honest, the border is too far removed from the industrial centres in Iraq, making transportation domestically, to and from the estate, too costly and uncompetitive. In other words, the hopes hung on these deals to rejuvenate trade and exports are a little too out of proportion,” warned Akel.

Like Ababneh, but contrary to his optimism, Marji also agrees that Jordan has lost its exclusive export advantage, “with Turkey, Iran and the US being the largest shareholders in the Iraqi market. There are also Saudi Arabia and the UAE to watch out for”.

There are still political barriers to the restoration of trade and ties in general between Iraq and the Arab Gulf, but it is only a matter of time, Marji noted.

Scrambling for foothold

“In almost all fields of exportation, the Saudis have developed industries that can easily drive Jordanian goods out of the Iraqi market, due to the competitive price offering and quality, not to mention that Jordan will soon be competing with the US via Saudi Arabia, as some of the world’s most prominent corporations — Procter and Gamble for instance — are producing and exporting out of Saudi Arabia.”

What remains for Jordan are some of the raw materials and minerals produced locally, such as phosphate and cement, which can hold a massive share in the Iraq market, but are not produced in enough quantities to compensate for the shrinkage of Jordan’s exports in foodstuffs, for example, or chemicals, Marji underlined.

“We can, of course, export ICT expertise and services, both directly and indirectly. This is a field we have a relative advantage in, compared with other economies in the region. We can certainly help with the Iraqi government’s digitisation effort, as well as other related fields,” the economist highlighted.

In regards to commodities, traditional exports in particular, Jordanian products stands a small chance, if the private sector does not immediately turns inwards to boost the quality of their exports, Marji stressed.

He contended that the Iraqi consumer would soon see less costly options, and that the confidence they have in Jordanian products will not withstand the abundance of suitable choices.

“There is appreciation for the Jordanian role over the years and confidence in Jordan, as a country, but there is little trust in Jordanian products, as Jordanian industrialists had often exploited the loose standards Iraqi authorities had set for Jordanian products,” Marji noted.

This came at the expense of confidence in Jordanian commodities, he continued.

Abu Wishah agreed with Marji, but argued that some exporters maintained a reputable level of quality and service, since before the US occupation of Iraq in 2003.

He stressed that the Iraqi importers do not stick to their previous impressions on the shortcomings of some of Jordan’s exporters in the time of the embargo on Iraq.

Apart from supply issues, there is the question of the Iraqi market itself, its own purchasing power and demand.

“Aside maybe to ICT, the Iraqi market has neither the demand nor the purchasing power to absorb massive quantities of other Jordanian exports, even if [our] industrialists magically managed to produce the quantities in question of specific commodities that other economies in the region do not produce,” Marji suggested.

Re-penetration

For example, Jordan’s total exports of phosphate in 2017 stood at some 5.2 million tonnes, amounting in value to some JD586 million, a Jordan Phosphate Mining Company (JPMC) statement in April 2018 said. Data provided by the Department of Statistics puts phosphate exports to Iraq in 2016 at JD371.6 million.

It should be noted that this particular mineral is readily available for export as a raw material, with minimal processing and manufacturing or development needed.

If Jordan were to focus solely on exporting phosphate to Iraq, the JPMC has to double its exports and split it evenly between Iraq and the rest of the world, for the economy to begin to compensate for the decline in demand for other exports driven out from the Iraqi market by competitors.

Combined, Jordan’s total exports of pharmaceuticals, fertilisers, raw phosphate and potash in 2017 amounted to some JD1.03 billion, at 23 per cent of the total export mix.

Jordan’s overall exports amount to around JD4.35 billion worth of goods and commodities, including national products and re-exports.

Although data by the Department of Statistics does not show Jordanian exports of phosphate and potash to Iraq in specific, they do show that among the Kingdom’s top industrial goods exported to Iraq in 2017 were pharmaceutical products and fertilisers, at JD61.8 million and JD47.3 million, respectively.

That said, Marji argued, is there demand in Iraq for these raw minerals and materials? If so, is there the purchasing power to consume and absorb these quantities?

Contrarily, Akel suggests that Jordan focuses on low-tech, low-cost products in order to re-penetrate the Iraqi market and not clash against the tides of Turkish and Iranian products.

Abu Wishah disagreed.

“We must not deny any exporter the chance to benefit from the opportunity presented by the underway and coming facilitation of exportation to Iraq.”

Focusing on one, two or three products will be counterproductive, he warned.

The governments of both Iraq and Jordan must do their part in regards to tax, custom and fee exemptions, as well as power cost reductions.

“Leave the rest to the private sector and the market to sort itself out, and our exports will surely regain their competitiveness and shares, not only in the Iraqi market, but beyond. The government must hurry in its promised facilities, which we have been waiting for since the beginning of 2018, before time runs out and our regional competitors leave no place for us; then the mission will be doubly impossible,” Abu Wishah concluded.

Achievable as it may be, Jordanian exporters are hopeful, yet worried, that the needed facilities to boost trade and competitiveness for their products may not come in time before the Iraqi market is completely overrun by rival commodities.

February 2 is the hour-zero for Jordanian-Iraqi trade ties, as much is promised to change, to rejuvenate what the Iraqi ambassador reaffirms to be an “exquisite”, mutually-beneficial relationship.

Latest News

Safadi, Iranian counterpart discuss war on Gaza, regional escalation

Safadi, Iranian counterpart discuss war on Gaza, regional escalation US vetoes Security Council resolution on full Palestinian UN membership

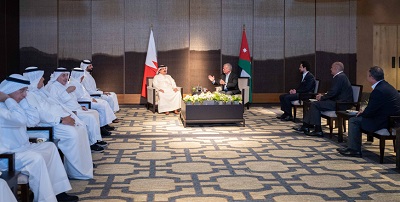

US vetoes Security Council resolution on full Palestinian UN membership King, Bahrain monarch stress need to maintain Arab coordination

King, Bahrain monarch stress need to maintain Arab coordination Security Council to vote Thursday on Palestinian state UN membership

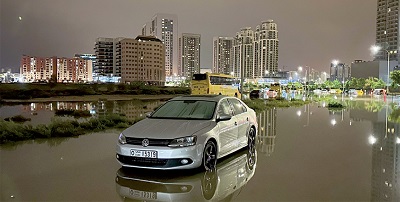

Security Council to vote Thursday on Palestinian state UN membership Dubai reels from floods chaos after record rains

Dubai reels from floods chaos after record rains

Most Read Articles

- Jordan urges UN to recognise Palestine as state

- Senate president, British ambassador discuss strategic partnership, regional stability

- JAF carries out seven more airdrops of aid into Gaza

- Temperatures to near 40 degree mark next week in Jordan

- Safadi, Iranian counterpart discuss war on Gaza, regional escalation

- UN chief warns Mideast on brink of ‘full-scale regional conflict’

- US vetoes Security Council resolution on full Palestinian UN membership

- Google fires 28 employees for protesting $1.2 billion cloud deal with “Israeli” army

- Biden urges Congress to pass 'pivotal' Ukraine, Israel war aid

- Israeli Occupation strike inside Iran responds to Tehran's provocation, reports say