Scientists urge ban of insecticides tied to brain impairment in kids

Reuters

Pregnant women should not be exposed to even low levels of a group of chemicals associated with a wide range of neurodevelopmental disorders in children, scientists argue.

Pesticides known as organophosphates were originally developed as nerve gases and weapons of war, and today are used to control insects at farms, golf courses, shopping malls and schools. People can be exposed to these chemicals through the food they eat, the water they drink and the air they breathe.

Restrictions on these chemicals have reduced but not eliminated human exposure in recent years. The chemicals should be banned outright because even at low levels currently allowed for agricultural use, organophosphates have been linked to lasting brain impairment in children, scientists argue in a policy statement published in PLoS Medicine.

“Exposure to these organophosphate pesticides before birth is associated with conditions that can persist into late childhood and/or pre-adolescence, and may last a lifetime,” lead author of the statement Irva Hertz-Picciotto, director of the Environmental Health Sciences Centre at the University of California Davis School of Medicine in California, told Reuters Health.

“Research on organophosphates now presents strong evidence that includes behavioural outcomes such as problems with attention, hyperactivity, full-blown ADHD, autistic symptoms or autism spectrum disorder or other behavioural issues,” Hertz-Picciotto said in an e-mail.

Despite growing evidence of harm, many organophosphates remain in widespread use. This may be in part because low-level, ongoing exposures typically do not cause visible, short-term clinical symptoms, leading to the incorrect assumption that these exposures are inconsequential, Hertz-Picciotto said.

“Acute poisoning is tragic, of course, however the studies we reviewed suggest that the effects of chronic, low-level exposures on brain functioning persist through childhood and into adolescence and may be lifelong, which also is tragic,” Hertz-Picciotto said.

Once the organophosphates enter the lungs or the gut, they are absorbed into the bloodstream, and can pass through the placenta to babies developing in the womb. From there, the blood can carry these chemicals to the developing brain.

To prevent prenatal exposure to these chemicals, the products should no longer be used for agricultural or other purposes, scientists argue. Water should also be monitored for the presence of these chemicals, and there should be a central system for reporting pesticide use and illnesses linked to the products.

Absent a complete ban on these chemicals, doctors and nurses should receive training to learn how to recognise and treat neurodevelopmental disorders related to exposure, and clinicians should also educate patients on how to avoid or minimise exposure.

Eating organic foods may also help curb exposure to pesticides, Hertz-Picciotto advised.

Pregnant women can also help prevent neurodevelopmental disorders in children by taking prenatal vitamins with folic acid and iron.

“We have known for several decades that high exposure to organophosphates can cause severe neurological impacts, and even death; this isn’t surprising, after all, because they were originally designed as nerve agents in the period between the two world wars,” said Dr Joseph Allen, director of the Healthy Buildings Programme at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

Since then, widespread use of these chemicals at lower levels in pesticides was assumed to be harmless to humans, Allen, who was not involved in the paper, said by e-mail.

“This was shortsighted,” Allen said. “The scientific evidence has piled up and it shows that even low-level, prenatal exposure can cause high-level, lifelong effects.”

Latest News

Security Council to vote Thursday on Palestinian state UN membership

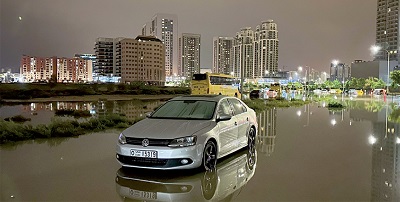

Security Council to vote Thursday on Palestinian state UN membership Dubai reels from floods chaos after record rains

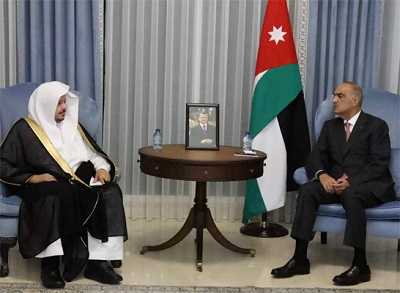

Dubai reels from floods chaos after record rains Khasawneh, Saudi Shura Council speaker discuss bilateral ties, regional developments

Khasawneh, Saudi Shura Council speaker discuss bilateral ties, regional developments Egyptian Foreign Minister condemns potential Palestinian displacement as 'war crime'

Egyptian Foreign Minister condemns potential Palestinian displacement as 'war crime' Travelers from Jordan advised to confirm flights amid Gulf weather turmoil

Travelers from Jordan advised to confirm flights amid Gulf weather turmoil

Most Read Articles

- King, Bahrain monarch stress need to maintain Arab coordination

- Dubai reels from floods chaos after record rains

- Security Council to vote Thursday on Palestinian state UN membership

- Khasawneh, Saudi Shura Council speaker discuss bilateral ties, regional developments

- Tesla asks shareholders to reapprove huge Musk pay deal

- Jordan will take down any projectiles threatening its people, sovereignty — Safadi

- Hizbollah says struck Israel base in retaliation for fighters' killing

- Princess Basma checks on patients receiving treatments

- Knights of Change launches nationwide blood donation campaign for Gaza

- The mystery of US interest rates - By The mystery of US interest rates, The Jordan Times