Is economics promoting inequality? - By Kaushik Basu, The Jordan Times

NEW YORK – These are harrowing times. Amid soaring inequality, political leaders in many countries are cutting programs and services that benefit the poor, while stoking fear and anger against migrants and refugees. Their noble-sounding intentions, safeguarding individual freedom, promoting prosperity, and protecting citizens, are often a fig leaf for a policy agenda designed to enrich themselves and their wealthy cronies.

This deterioration in the practice of politics can be attributed to many causes. One of the most important may be found in the deterioration in how economics is practiced.

Economics is often described as a scientific discipline, which studies “if-then” propositions without reference to morals and values. But scientific findings do affect our values and normative judgments, and claims of “scientific objectivity” can be used to rationalize actions that offend our moral sensibilities. In fact, the logic of mainstream economics – in particular, the long-dominant neoliberal ideology, which emphasizes growth, efficiency, and market freedom – has often justified and even encouraged greed, exploitation, and extreme inequality.

This may well be built into the discipline. A 2012 study based on the Nobel laureate economist Amartya Sen’s “capability approach” – a framework for evaluating economic arrangements that focuses on people’s ability to live the kinds of lives they value, not simply on material wealth – found that some educational approaches can help make people more caring and cooperative. But other studies indicate that students of economics tend to behave more selfishly than others, indicating that economics, as it is taught, may well promote selfishness as a normal or even desirable ethical principle.

The problem, argued another Nobel laureate economist, the late Kenneth Arrow, in a relatively unknown 1978 paper, is that the “model laissez-faire world of total self-interest” that neoclassical economics envisions “would not survive for ten minutes” in a “world of any complexity.” Markets cannot function unless economic actors, even “competing firms and individuals,” reliably honor “reciprocal obligations.” In other words, they depend on trust and cooperation.

Arrow also challenged the tendency of mainstream economics to treat freedom and equality as contradictory. The neoliberal logic is that any amount of inequality is natural and fair, and thus any intervention to reduce it erodes freedom: one reaps what one sows. If you are very wealthy, you must have earned it, such as through hard work or innovative thinking, and you should be “free” to enjoy the spoils of your contributions.

But, as Arrow pointed out, when “a few” are making the “major decisions on which human welfare depend[s],” they are doing so “in their own interests.” In his view, freedom and equality were “close to identical” in “many contexts.” Actions that undermine equality – such as strike-breaking and “more subtle forms of economic pressure” – cause the “freedom of workers” to be “much restricted,” and the “absorption of the economy by a small elite” implies that “formal democracy and freedom” are a “sham.” Ultimately, Arrow wrote, “institutions that lead to gross inequalities are affronts to the equal dignity of humans.”

The philosopher Isaiah Berlin put it succinctly: “freedom for the wolves has often meant death for the sheep.” This warning is especially prescient today, when the “wolves” have enormous resources to channel toward the political leaders and causes of their choosing, as well as unprecedented digital tools for influencing public opinion. As yet another Nobel laureate economist, Joseph E. Stiglitz, observed, the principle of “one person, one vote” has given way to “one dollar, one vote.”

But an excessive focus on economic self-interest is only part of the problem. Virulent nationalism is also contributing to rising inequality.

There was a time when the nation-state was a vital institution for organizing economic life, and national pride had a role to play in supporting progress. But in our globalized world, cross-border flows of people, goods, and capital are both inescapable and important drivers of prosperity – not least for the wealthiest few. At the same time, the super-rich and the politically powerful often cynically stoke nationalism to advance their interests. It is a time-tested formula: people who are fighting wars in defense of the “nation” will not mobilize against inequality of wealth or power – and may even increase it.

National pride is a relic of the past. Now is the time for global cooperation on collective goals, from mutually beneficial trade arrangements to just and inclusive climate action. But getting there will not be easy: like functioning markets, multilateral action on shared challenges depends on trust and cooperation.

The French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s stag-hunt game illustrates the challenge. If two hunters each hunt a hare alone, the reward is small but certain. If they choose to hunt a stag together, they stand to gain far more, but only if they can count on each other to do their part; otherwise, they end up with nothing. Likewise, by bolstering faith in cooperation, multilateral organizations like the International Labor Organization and the International Court of Justice can help countries to achieve more than they ever could on their own.

But strengthening these and other cooperative institutions will require us to recalibrate our moral compass. Rather than viewing an exclusive focus on self-interest as “rational,” or limiting our compassion to those who look, sound, or pray like us, we must value humanity more than nationality.

Kaushik Basu, a former chief economist of the World Bank and chief economic adviser to the Government of India, is Professor of Economics at Cornell University and a non-resident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2025.www.project-syndicate.org

Latest News

-

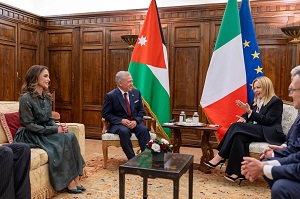

King, Italy PM call for ensuring implementation of Gaza agreement

King, Italy PM call for ensuring implementation of Gaza agreement

-

King, Queen meet with Pope Leo XIV

King, Queen meet with Pope Leo XIV

-

Russia accused of targeting UN aid convoy in southern Ukraine’s Kherson region

Russia accused of targeting UN aid convoy in southern Ukraine’s Kherson region

-

'Israel' won’t reopen Rafah crossing over Hamas’s failure to return captives’ bodies: Hebrew media

'Israel' won’t reopen Rafah crossing over Hamas’s failure to return captives’ bodies: Hebrew media

-

'Israel' returns 45 Palestinian bodies to Gaza as past organ theft allegations resurface

'Israel' returns 45 Palestinian bodies to Gaza as past organ theft allegations resurface