The Daily Star

BEIRUT - Alexandre Najjar’s 2013 travelogue “Les Anges de Millesgarden” (The Angels of Millesgarden) was inspired by the francophone author’s travels around Sweden.

“This book is not,” as Najjar wrote in his first sentence, “a guidebook to Sweden.”

The author found himself in the Scandinavian country to present a series of lectures on Lebanese artist Khalil Gibran (whose biography he’d penned in 2002), francophone culture and the role of the writer.

“During this trip,” Najjar writes, “I didn’t want to imitate Japanese tourists who ... take pictures of anything that moves and doesn’t move: I preferred to behave as an observer of the local customs, [in reference to] certain Orientalists.”

Najjar’s book is an erudite literary project. More than a mere guidebook, it examines the truth and fiction underlying its national stereotypes, as well as the foundational importance of the arts, literature and languages in Swedish culture.

In a radio interview about his book on France Info, Najjar recalled how, “as a Middle Eastern [man, he] was stunned by this country. [Sweden] is at the geographical, sociological and historical antipode of Lebanon. [He] felt that everything that didn’t work [in Lebanon], worked over there.”

“Les Anges de Millesgarden” provides a panorama of a culture quite alien to the author’s experience – and arguably to that of most of his countrymen. Often characterized as a model of democracy and equality among its citizens, Sweden is depicted from the perspective of an author who wonders “why a small country of 4 million inhabitants – considered as ‘Switzerland of the Middle East’ – failed where Sweden succeeded?”

There is something self-consciously quaint in Najjar’s account. Each of his book’s chapters is given a title evocative of 19th-century novelistic convention: “Where we discover Stockholm airport, taxis, snow, Bernadotte and alcohol,” say, or “Where we pay a visit to Greta Garbo,” “Where we visit the Nobel Museum and the Swedish Academy” or “Where we discover the educational system and war through the eyes of young Swedes.”

For almost 200 pages, the reader is drizzled with information about Swedish culture, a storm offset every now and then with comparative glances at Lebanon’s cultural landscape. This contrapuntal approach enables Lebanese readers to empathize with Najjar’s journey of discovery.

Arriving at the Stockholm airport, for instance, the author remarks that “each year, more than 500 couples get married [there.]” Not only would it be considered eccentric for a Lebanese couple to be wed at Rafik Hariri International Airport, but whoever chose to do would likely be considered stingy or downright mad.”

Najjar devotes extensive passages to describing Sweden’s natural beauty. Green spaces, not infrequently dappled with snow, are considered as integral to society’s growth and well-being as property development.

In Lebanon, he notes, “the equation is reversed ... nature capitulates to the hegemony of concrete; the country – that has landscapes of great beauty – is disfigured by anarchic constructions and rubbish dumps.”

Najjar’s work is replete with numerous literary references, both from the Middle East and the West. Abu Nawas’ ode to wine is recalled. Mme de Stael’s remarks on Sweden’s seasons are quoted, as is Voltaire’s thoughts on Descartes’ death.

His title “Les Anges de Millesgarden” alludes to Stockholm’s famed Millesgarden art museum and sculpture garden, situated in the island home of the late Carl Milles and his wife, and fellow artist, Olga Milles.

One of Sweden’s most venerated artists, Carl Milles is renowned for his sculptures of angels. Captured in a variety of poses – from (eccentrically) checking his watch to playing instruments – they tend to be erected atop tall thin columnlike plinths, accentuating their ethereal nature.

The author also takes his readers along to the Moderna Museet (Stockholm’s Museum of Modern Art), the Museum of Architecture and the National Museum of Fine Arts. The works of Jan Massys, Jacob Jordaens, Rembrandt, Picasso and Chagall mingle within a society that Najjar – quoting his friend Laurent, Millesgarden’s gardener – describes as “paradise.”

Lest his readers find his depictions of Sweden to be a trifle worshipful, Najjar punctuates and contextualizes his personal travelogue with asides to Swedish history, that is, tales of the country’s monarchs.

When he ascended to the Swedish crown in the early 19th century, Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte chose the name Charles XIV John. Descartes’ student Queen Christina apparently forced the French philosopher to administer lessons at 5 a.m. in a badly heated library.

Perhaps the funniest historical reference alludes to King Gustave V, an avid tennis player who competed under the alias “Mr. G.”

Other hilarious facts are called up to illustrate the Swedish condition. One law, for instance, forbids parents to name a child such eccentric names as “Ikea” or “Dark Knight.”

Much of the book is well worth citing, but it would be best to read them yourself.

Alexandre Najjar’s “Les Anges de Millesgarden” is published in French by Editions Gallimard and is available is select local bookstores.

Latest News

-

King meets with retired brothers-in-arms from Special Forces

King meets with retired brothers-in-arms from Special Forces

-

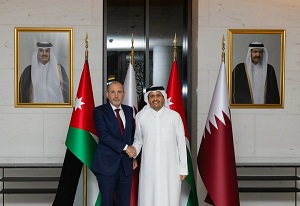

Foreign Minister, Qatari prime minister discuss bilateral ties, Gaza developments

Foreign Minister, Qatari prime minister discuss bilateral ties, Gaza developments

-

Jordan beats Egypt to reach 9 points at top of group C in Arab Cup

Jordan beats Egypt to reach 9 points at top of group C in Arab Cup

-

Netanyahu to Meet Trump on December 29

Netanyahu to Meet Trump on December 29

-

Hamas says no Gaza truce second phase while Israel 'continues violations'

Hamas says no Gaza truce second phase while Israel 'continues violations'