Economic fragility and technical rigidity: Jordan’s energy sector in focus - By Mohammed Dabbas, The Jordan Times

|

A recent policy paper by the Centre for Strategic Studies has reaffirmed what many experts have long argued: Jordan’s energy sector is a striking example of how economically fragile policies and inflexible technical systems can intersect — with costly consequences. This entanglement has produced growing financial burdens, structural inefficiencies, and the erosion of strategic opportunities.

For more than a decade, the sector has been caught in a cycle of delayed reforms and ad hoc decision-making. During this period, public debt has soared, competitiveness has declined, and the gap between production costs and end-user pricing has widened. Addressing these challenges is no longer optional; it is a national imperative.

The origins of Jordan’s electricity crisis can be traced back to the disruption of Egyptian gas supplies following the Arab Spring. This forced the country to rely on expensive traditional fuels. While the government chose not to pass on these costs to consumers at the time, the financial toll was significant. By 2024, the National Electric Power Company (NEPCO) had amassed over JD 6 billion in debt — representing 14.5 per cent of Jordan’s total public debt and approximately 16.7 per cent of its GDP.

Although the partial resumption of gas flows and the signing of new energy agreements helped reduce operational costs, the structural crisis has not abated. In fact, it has deepened. Jordan committed to long-term renewable energy and oil shale projects under “take-or-pay” contracts — arrangements that obligate the government to pay for energy whether it is used or not. With demand in decline, these contracts have widened the fiscal deficit and kept overall costs elevated.

To recoup losses, the government has resorted to raising electricity tariffs. However, this strategy risks alienating large consumers, who may either disconnect from the grid or significantly cut their usage. This not only undermines revenue collection but also increases capacity charges — fees paid for energy infrastructure that remains underutilised.

Jordan urgently requires a comprehensive overhaul of its energy sector governance. This must include a more responsive, incentive-driven tariff structure that shields productive sectors from excessive costs. Simultaneously, the country should seek to capitalise on surplus capacity through electricity exports to neighbouring states.

Support for electric vehicles (EVs) should also be strengthened. Beyond their environmental benefits, EVs can contribute to economic growth, technological advancement, and improved energy efficiency.

In conclusion, Jordan’s energy sector lays bare the risks of rigid policy frameworks and long-term technical planning that fails to adapt to evolving market conditions and innovation. If the status quo persists, it will continue to sap economic productivity, strain public finances, and compromise quality of life. However, with bold reforms and a future-oriented strategy, the energy sector could shift from being a fiscal liability to a driver of sustainable national development.

Latest News

-

Legal expert outlines repercussions for Muslim Brotherhood financial scheme in Jordan

Legal expert outlines repercussions for Muslim Brotherhood financial scheme in Jordan

-

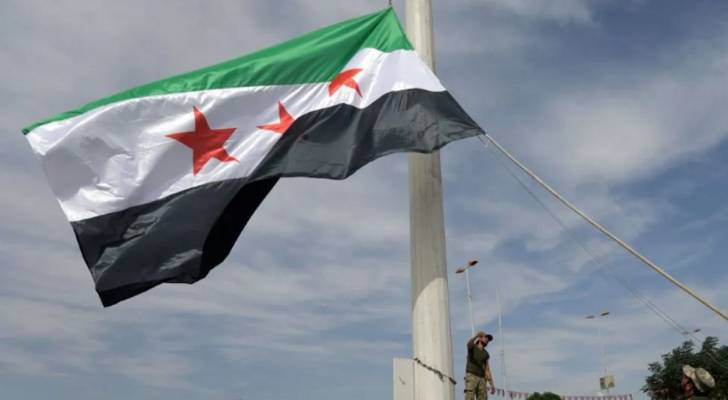

“Israeli” military attacks Syrian army headquarters

“Israeli” military attacks Syrian army headquarters

-

Over 30 million JD: Jordan authorities uncover massive Muslim Brotherhood covert funding scheme

Over 30 million JD: Jordan authorities uncover massive Muslim Brotherhood covert funding scheme

-

Syria announces ceasefire in Druze-majority Suwayda after deadly clashes

Syria announces ceasefire in Druze-majority Suwayda after deadly clashes

-

“Israel” says striking Syrian govt forces in Suwayda

“Israel” says striking Syrian govt forces in Suwayda