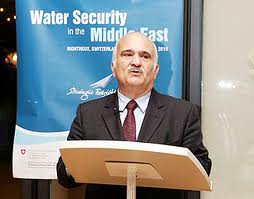

Water Cooperation for a Secure World - By Prince Hassan bin Talal, Al-Monitor

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has repeatedly emphasized the need to explore the linkage between water, peace and security. Now, new research by the Strategic Foresight Group demonstrates that he has been right to do so. Empirical evidence in 148 countries and 205 shared river basins indicates that any two nations engaged in active water cooperation do not go to war.

Of the 148 countries covered by the report "Water Cooperation for a Secure World," 37 are at risk of going to war over issues other than water, including land, religion, history and ideology. These also happen to be precisely the 37 countries which do not engage in active water cooperation with their neighbors.

The good news is that more than a hundred of those countries which promote water cooperation in both letter and practice also enjoy peaceful and secure relationships with their neighboring countries. Water and peace are interdependent.

Despite the growing international consensus in the international community on the significance of water as an instrument of cooperation (as reflected in the UN’s designation of 2013 as the Year of Water Cooperation), many analysts continue to project water as a source of potential conflict. It is true that lakes, rivers and glaciers around the world are shrinking. Growing pressures of population, economic growth, urbanization, climate change and deforestation can further deplete water resources, thus causing social and economic upheavals, but this need not be so.

Active water cooperation can help overcome environmental challenges and usher in a new era of peace, trust and security. Beyond the essential legal agreements, active cooperation also requires sustained institutions of trans-boundary cooperation; joint investment programs; collective management of water-related infrastructure; a system for regularly and jointly monitoring water flows together with a shared vision of the best allocation of water resources between agriculture and other sectors; and a forum for frequent interaction between top decision-makers. An institutional infrastructure should enable political leaders to discuss exchanges between water and other public goods such as transit, national security or large public works. The underlying emphasis must be placed on harnessing the benefits of a river, rather than on squabbling about the shares of depleting flows.

The new Strategic Foresight Group report introduces the water cooperation quotient (WCQ), which measures the effectiveness and intensity of trans-boundary cooperation in water using the parameters mentioned above. The 37 countries that face the risk of war happen to have a WCQ below 33.33.

Many parts of the world witness active water cooperation between riparian countries. In the Senegal River Basin in West Africa, an autonomous body independent from any state owns the dams. In Latin America, the waters of Lake Titicaca are considered joint and indivisible by Peru and Bolivia. In the Mekong Basin, flow data is harmonized among the lower riparian countries, while the upper riparian countries, China and Myanmar, are dialogue partners. The Rhine, Danube and Sava River Basins, as well as Lake Constance in Europe and the Colorado River between the United States and Mexico, are all jointly managed on a daily basis. These countries all enjoy peaceful and stable relations.

The benefits of active water cooperation — both in terms of economic growth and in previously unknown levels of peace, as evidenced in both the developed and parts of the developing world such as Central America, West Africa, and Southeast Asia — should not be denied to West Asia or other regions. Such cooperation, however, is premised on an intellectual framework for cooperation, rather than confrontation, or the “Blue Peace way of thinking” where water is seen as an instrument of collaboration rather than a cause of crisis.

We have together developed the Blue Peace approach in a process supported by the Swiss and Swedish governments over the last three and a half years. It entails the development of a community of political leaders, parliamentarians, government officials, media leaders and experts from regions facing political discord, to encourage the use of water to promote peace and to protect and enhance the human environment. Such a community can pave the way to establish regional cooperation councils for the sustainable management of trans-boundary waters to facilitate joint monitoring of water flows; to harmonize standards to measure water and climate indicators; to negotiate joint investment plans in water-related large projects; and to discuss exchanges between water and other public goods. This can result in the improvement of the WCQ to a level higher than 33.33 in Asia and Africa. Indeed, we urge all countries to use the WCQ to assess their own performance with regard to their cooperation with neighbors and thereby to enhance the prospects of peace and security for themselves.

It is our profound hope that together we can begin the process of implementing the Blue Peace framework across the world by crafting institutional instruments, globally acceptable legal regimes, dialogue mechanisms and a worldwide Blue Peace network. If we take a few steps in this direction this year, the proclamation of 2013 as the International Year of Water Cooperation will prove to be meaningful.

Latest News

-

Iran war sends oil price soaring as Khamenei son takes charge

Iran war sends oil price soaring as Khamenei son takes charge

-

King visits JAF General Command, commends efforts of army, security agencies in protecting Jordan

King visits JAF General Command, commends efforts of army, security agencies in protecting Jordan

-

US, Israel hit five oil sites in and near Tehran: official

US, Israel hit five oil sites in and near Tehran: official

-

Trump says new Iran leader won't last long without his approval

Trump says new Iran leader won't last long without his approval

-

Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia condemn Iran’s attacks on Arab states

Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia condemn Iran’s attacks on Arab states